New research proves a popular, painful IVF procedure does not work

Endometrial scratching has been touted as a strategy to help women conceive, but new research proves that the painful intervention isn’t necessary – or effective – after all.

Painful, pricey, pointless

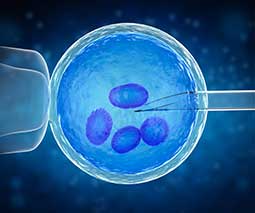

Fertility clinics offer endometrial scratching as a technique aimed at improving the success rates of embryo implantations.

The procedure involves a catheter being passed through the cervix and scratching the lining of the uterus to cause a superficial wound.

Some small trials had previously suggested that the scratch may spark an inflammatory response which helps the embryo ‘stick’ to the uterine wall.

It’s a pricey and painful technique often carried out on women who have already undergone multiple failed rounds of IVF.

Read more about IVF:

- What are my options when it comes to my unused embryos?

- Sophie Monk Instagrams her egg retrieval procedure

- A new business is giving grants to those struggling with the cost of IVF

- Australian parents-to-be given access to life-changing genetic testing

Three year study

University of Auckland researchers hope the technique will be shelved altogether. They’ve just published the findings of their study into endometrial scratching in the New England Journal of Medicine. During three years of trials across 13 fertility centres in New Zealand, the UK, Belgium, Sweden and Australia, the team monitored the IVF treatments of 1364 women.

They randomly assigned half the women the endometrial scratching procedure ahead of their IVF, and the other half underwent IVF only – without the painful scratching. The results show that the frequency of live birth was 26 percent in the endometrial-scratch group and 26 percent in the no-scratch group. Same-same.

There were no significant between-group differences in the rates of ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, or miscarriage.

“Stop offering this”

The paper concluded that “endometrial scratching did not result in a higher rate of live birth than no intervention among women undergoing IVF.”

“We would recommend that clinics stop offering this,” lead study author Sarah Lensen told Reuters Health.

In Australia, the head of the Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority (VARTA) – which supports families struggling with fertility issues – said this information was very important.

“This study provides the opportunity to tell patients that the evidence doesn’t stack up,” VARTA’s Louise Johnson told the ABC.

“Couples going through IVF are extremely vulnerable, and clinics have an obligation to inform patients about treatments that can cause pain and won’t increase the chance of conception,” Louise explained.