Women aren’t better multitaskers than men – they’re just doing more work

Multitasking has traditionally been perceived as a woman’s domain. A woman, particularly one with children, will routinely be juggling a job and running a household – in itself a frantic mix of kids’ lunch boxes, housework, and organising appointments and social arrangements.

But a new study, published today in PLOS One, shows women are actually no better at multitasking than men.

The study tested whether women were better at switching between tasks and juggling multiple tasks at the same time. The results showed women’s brains are no more efficient at either of these activities than men’s.

Using robust data to challenge these sorts of myths is important, especially given women continue to be bombarded with work, family and household tasks.

No one is good at multitasking

Multitasking is the act of performing several independent tasks within a short time. It requires rapidly and frequently switching attention from one task to another, increasing the cognitive demand, compared to completing single tasks in sequence.

This study builds on an existing body of research showing human brains cannot manage multiple activities at once. Particularly when two tasks are similar, they compete to use the same part of the brain, which makes multitasking very difficult.

But human brains are good at switching between activities quickly, which makes people feel like they’re multitasking. The brain, however, is working on one project at a time.

In this new study, German researchers compared the abilities of 48 men and 48 women in how well they identified letters and numbers. In some experiments, participants were required to pay attention to two tasks at once (called concurrent multitasking), while in others they needed to switch attention between tasks (called sequential multitasking).

The researchers measured reaction time and accuracy for the multitasking experiments against a control condition (performing one task only). They found multitasking substantially affected the speed and accuracy of completing the tasks for both men and women. There was no difference between the groups.

Domestic duties

My colleagues and I recently busted another relevant myth – that women are better at seeing mess than men. We found men and women equally rated a space as messy. The reason men do less cleaning than women may lie in the fact that women are held to higher standards of cleanliness than men, rather than men’s “dirt blindness”.

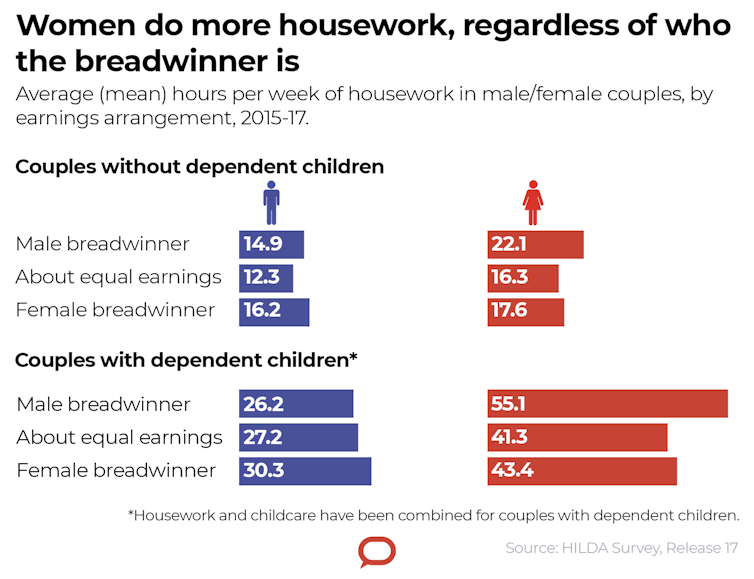

Recent data shows Australian men are spending more time doing domestic work than they used to, but women still do the vast majority of the housework.

Working Australian women have seen their total time across work and family activities increase over time, with bread-winning mothers spending four hours more across these activities per week than bread-winning fathers.

This means working mums are balancing planning birthday parties, childcare drop-offs and ballet lessons all on top of their regular jobs, commutes and careers.

Consequences of the myth

If women’s brains are equally strained by multitasking, why do we keep asking women to do this work? And, more importantly, what are the consequences?

Our recent study shows mothers are more time-pressed and report poorer mental health than fathers. We found the birth of a child increases parents’ reports of feeling rushed or pressed for time, but the effect is twice the size for mothers than it is for fathers. Second children double mothers’ time pressure again and, as a consequence, lead to a deterioration in their mental health.

Women are also more likely to drop out of paid work when children are born or family demands intensify. They carry a larger mental load tied to organising the needs of the family – who has clean socks, who needs to be picked up from school, whether there is enough Vegemite for lunch. All of this labour is at the expense of time planning for the next day’s work, the next promotion, and so on.

Women are also asked to multitask family demands at night. Children are more likely to interrupt their mother’s than their father’s sleep.

Although gender roles are changing and men are assuming a larger share of the housework and childcare than in the past, gender gaps remain in many important domains of work and family life. These include the allocation of childcare, the division of housework, the wage gap, and the concentration of women in top positions.

So, the multitasking myth means mothers are expected to “do it all”. But this obligation can affect women’s mental health, as well as their capacity to excel at work.

Challenging misconceptions

Public opinion persists that women have a biological edge as super-efficient multitaskers. But, as this study shows, this myth is not supported by evidence.

This means the extra family work women perform is just that – extra work. And we need to see it as such.

Within the family, this work needs to be catalogued, discussed and then equally divided. More men today are invested in gender equality, equal sharing and co-parenting than ever before.

As well as in the home, we need to dismantle these myths in the workplace. The assumption women are better multitaskers can influence the allocation of administrative tasks. Tasks, like taking minutes and organising meetings, should not be allocated based on gender.

Finally, governments need to dismantle these myths within their policies. Children add work that cannot be easily multitasked. Women need affordable, high-quality, and widely available childcare.

Men also need access to flexible work, parental leave and childcare to share in this labour, and protections to ensure they aren’t penalised for taking time to share in the care.

Debunking these myths that expect women to be superheroes is a good thing, but we need to go further and create policy environments where gender equality can thrive.![]()

Leah Ruppanner, Associate Professor in Sociology and Co-Director of The Policy Lab, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.