“I’d never heard of GBS but if I had it could have saved my unborn baby’s life”

Losing my daughter was hard enough but knowing a simple course of antibiotics could have saved her made her death almost impossible to accept.

Warning: this post discusses infant loss and features images and content that could distress some readers.

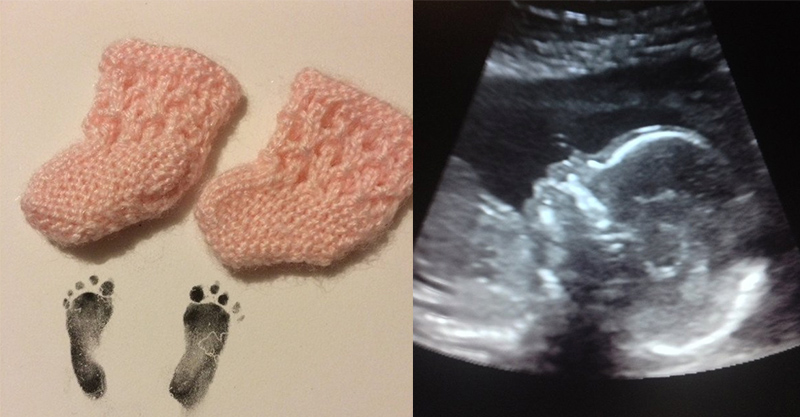

One moment I was watching her kick and bounce on screen during an ultrasound, excitedly revealing her gender to family and friends via text, completely unaware that in less than 10 hours I would be holding her in my hands as she tried to breathe.

The bacteria that changed my life

I would later come to find out I had contracted Group B Streptococcus (Group B Strep, or GBS), a bacteria naturally found in the digestive and reproductive tracts of men and women that can be present in the vagina of pregnant women and passed on to their baby during birth – or in very rare cases like mine, through the placenta – if left undetected.

It is so common that about one in four pregnant women are carriers. For most pregnant women in Australia there will be no symptoms or negative repercussions but for the 12 to 15 percent of women who do, the latest research finds that of the babies who contract it from their mother, 6 percent of those cases will be fatal for the baby.

In my case, GBS caused me to go into premature labour when I was just 18 weeks pregnant.

Pregnant and tired but happy

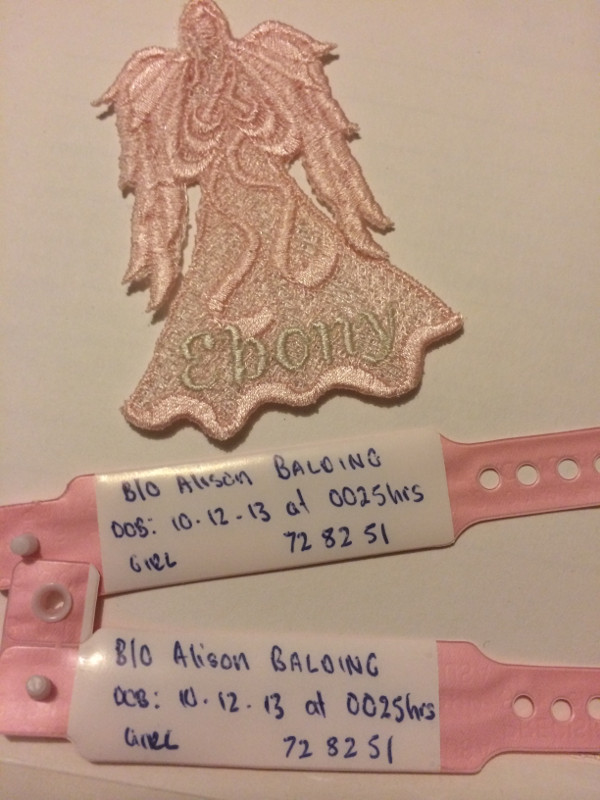

Ebony Alice Balding was meant to arrive on Mother’s Day in 2014. My husband and I called her ‘our natural miracle’ because we conceived her the traditional way just months after a long fight with infertility produced our son Oliver – ‘our IVF miracle’.

Caring for Oliver and being pregnant was exhausting but I was so happy and felt so blessed, I just got on with it. I can recall many people telling me I looked tired, encouraging me to take it easy and even offering to watch my son so I could take a nap. But I was determined to prove to them, and myself, I could handle it – after all, it’s what I asked for.

My husband decided I needed a night off so for our sixth wedding anniversary, he surprised me by getting two of my girlfriends to babysit so he could take me out to dinner. It was such a great night, we talked about how much our lives had changed for the better with our son and we admitted our nerves at having two children aged under 15 months. We also speculated whether we thought we were having a girl or boy, we were excited for either.

Losing baby Ebony

Soon after we returned home from dinner, I began cramping and noticed light blood spotting when I went to the toilet. I had passed a clot around the same stage of pregnancy with my son so I wasn’t too alarmed. The next morning I called my midwife when the spotting continued and she told me to head to emergency to get checked out.

I spent the morning in emergency waiting for test results, the spotting was heavier now but bub was kicking away. The doctor came back to me at 2pm with a script for antibiotics and told me to go home. They weren’t able to get me any results until the next day so I insisted on an ultrasound. There she was, all her vitals were good and she was bouncing around. The woman doing the scan confirmed the gender and even said, ‘she is perfect’.

I went home at about 4pm feeling very tired, the bleeding was heavier and I was questioning whether I should have left the hospital. Within three hours, the cramps were coming in waves and by 9pm I was convinced they were actually contractions.

I returned to hospital by 10pm but, being under 20 weeks pregnant, I had to wait again in emergency. By 11pm my waters broke and just after midnight on December 10, 2013, I gave birth to my little girl. Her lungs weren’t developed enough for her to be able to survive and I will never forget the sound she made as she struggled to breathe. I was so confused because it all just happened so quickly and it was so unexpected.

What went wrong?

It wasn’t until my six week check up after her death that doctors explained the test results which showed I had GBS. An infection had somehow passed from me, through the placenta and to my little girl.

I felt dirty

Hearing that bacteria, likely from my vagina, had killed my little girl made me feel violently ill. I was so ashamed and the guilt was overwhelming. Without going into too much detail, I consider myself to be a very clean person – regular showers, very particular about toilet cleanliness and an avid hand washer. If I had noticed anything of concern, be it a funny discharge or smell, I would have had no shame in seeking medical help.

After all the invasive scans and procedures I had endured to become a mum, there’s no shyness left when it comes to discussing that department and I certainly wouldn’t take any risks. But as I later discovered, anyone can have GBS and it does not mean you are unclean.

Symptoms to look for

It turns out in many cases, GBS exists in the body without having any effect all – no signs, no symptoms and causes no problems. In others, symptoms can include unusual vaginal discharge, burning or irritation that is often mistaken as a yeast infection. I had no symptoms but I did feel really run-down.

Risks to baby

While the bacteria is common and anyone can carry it, it is less common for GBS to be passed on to baby before birth – about one in 1000. However, if it does, it can cause premature labour, miscarriage, stillbirth and can cause baby to become very sick through a blood infection or sepsis, meningitis (swelling of the brain) and pneumonia.

GBS can also cause the baby to die soon after birth or leave the baby with permanent disabilities such as deafness, blindness, cerebral palsy and mental challenges.

Prevention

Early detection is vital to ensuring bub is given a fighting chance against GBS. I am almost 33 weeks pregnant with my third child and I insisted on being swab tested for GBS early on – completely clear. I will also be requesting a full urine culture test when I am between 35 and 37 weeks because women who test positive can prevent most GBS infections at birth by having four hours of IV antibiotics just prior to delivery.

This screening is routinely done in the US but not in Australia.